Pulling Back the Curtain on Fake Rum

Part I: Discovery of Deceit

There’s a common refrain on rum forums that says “drink what you like, but know what you’re drinking.” It’s a sentiment often used to soften the blow of telling someone a rum they like has added ingredients.

Sadly it’s not uncommon for new rum enthusiasts to discover a rum they once loved is a lie. The color didn’t come from barrels, the sweetness didn’t come from molasses, and the smoothness didn’t come from the distiller’s exceptional abilities. Rather, the aforementioned organoleptic qualities came from a host of ingredients known only to the unscrupulous blender who added them to the distillate.

The real tragedy in this is not that we discover a once-loved rum contains non-rum ingredients, it’s the fact that market acceptance of such products redefines the very meaning of rum for the consumer and imposes a huge impediment to the premiumization of the category in general, and pure rum in particular.

Added sugar in rum is the issue that gets most of the attention in this context, partly because one, we can perceive it on the palate, and two, we can measure it with a hydrometer. But what of the other additives?

Cyril from Du Rhum shed significant light on the subject of additives in this piece where he touched on a number of other additions including vanilla extract and glycerin, going so far as to send samples for lab analysis on these parameters. Re-reading Cyril’s piece recently made me recall several conversations I’d had with various rum experts over the past seven years in which the tricks of the unscrupulous blender were exposed. Absent access to advanced analytical equipment such as GC-MS, it’s very difficult to prove such additions are present, but what if we approach the issue in reverse by transparently making our own fake rum? Sounds like a fun and potentially illuminating exercise, so let’s give it a go.

Part II: Recreating the Lie

First let’s take a look at a dozen tools often found in the “rum” blender’s toolkit:

- Spirit caramel: Made from burnt sugar, it’s widely accepted for creating color consistency within a product line.

- Sweetener: regardless of form, sweeteners are added to excite the amygdala and create the impression of fullness, roundness, or smoothness. Most use sugar, but some blenders may also be using non-nutritive sweeteners to avoid detection; these come with associated bitterness. Additionally, at least one flavored rum producer is known to use high fructose corn syrup.

- Fortified wines: sweet fortified wines like Pedro Ximenez Sherry are powerful adulterants that add four components including color, sweetness, oak, and rancio.

- Glycerin: this viscous and powerfully sweet sugar alcohol can simultaneously add sweetness and smoothness to a spirit.

- Vanillin: vanillin can be derived from charred oak barrels of course, but in this context, it’s typically found in a bottle of vanilla extract.

- Oak essence (boisé): made by boiling charred oak chips in water or macerating them in neutral spirit, oak essence gives the impression of age without the wait.

- Dried fruits: raisins and prunes can be boiled in water to make a syrup or they can be macerated directly in the spirit. The result of these additions yields sweetness, complexity, and a bit of rancio.

- Nut extracts: this one appears to be used less often, but there are a few products out there whose nuttiness go far beyond what fortified wine rancio could ever do.

- High ester rum: a little high ester Jamaican rum can go a long way to making a neutral spirit taste like legitimate rum.

- Rum flavor: flavor houses make all manner of natural and artificial flavors, and rum is definitely one of them. Does it taste like rum? Not even remotely, but a lie told often enough becomes the truth, as they say. This one is responsible for those artificial fruit flavors you may have noticed in “dark” rums.

- Molasses: If you’ve ever tasted molasses wine, you know it doesn’t exactly taste like molasses. But you know what does? Molasses!

- Propylene glycol: Adds “smoothness” and roundness to a spirit’s mouthfeel.

There are certainly other tricks up the blenders’ sleeves, but these are ones I’m convinced are in use today, so let’s roll with these for now.

For the base of our fake rum, I bought the cheapest white rum I could find—just $11.99 for a 1.75 liter bottle. It just screams quality, doesn’t it?

To this base rum we’ll systematically add various blending ingredients to try and achieve the appearance and flavor profile of different aged rums.

First let’s establish the baseline tasting notes for the white rum base:

Appearance: Perfectly clear

Nose: Ethanol, touch of brine and black pepper, a hint of vanilla and caramel. Overall very vodka-like.

Palate: Very hot on the palate, a bit of fruit bursts on the tongue before giving way to a hint of vanilla and then black pepper. Very one-dimensional.

Now that we have a baseline, let’s attempt to achieve a few different target profiles. We’ll try and create a Jamaican style rum, a Central American style rum, a Cuban style rum, and finally a “dark” rum. The Central American style rum should be easy to imitate given the historical use of additives such as Sherry and sugar. The Cuban and Jamaican styles will undoubtedly be more difficult considering their general lack of additives. The “dark” rum should be the easiest, as rums made in this style are often nothing more than white rums with a bunch of added flavors.

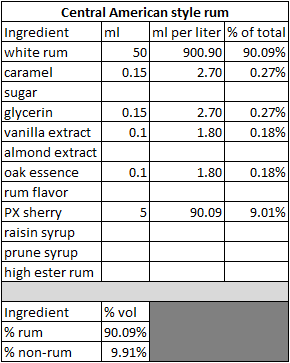

Here’s what we came up with:

Formula 1: Jamaican style rum

Appearance: Deep straw to gold. A quick set of legs forms and falls rapidly.

Nose: Roasted pineapple leaps out of the glass, followed by dark fruit and vanilla.

Palate: The pineapple leads the way, attenuating the ethanol burn. Subsequent sips prove the persistence of the pineapple, but vanilla and dark fruit come out with a bit of effort, as does some oak and black pepper.

Finish: Once again, the pineapple masks both the heat and the bitterness of the base rum.

Formula 2: Central American style rum

Appearance: Deep mahogany. An oddly spaced set of legs forms and falls slowly.

Nose: Prunes and Sherry-like rancio spring forth and are joined by sweet caramel and vanilla.

Palate: Sweet entry leads with an unmistakable Sherry note that yields raisins, prunes, and roasted nuts. The sweetness almost completely masks the heat and bitterness of the base rum. Subsequent sips are fairly enjoyable, bringing cooked fruit and notions of fruitcake and other baked goods.

Finish: A bit bitter, but it’s the Sherry that lingers longest.

Formula 3: Cuban style rum

Appearance: Deep copper mahogany. A swirl releases a uniform set of liberal legs. Once fallen, a secondary set of legs falls from larger droplets.

Nose: A dose of ethanol is followed by oak and vanilla. A slight hint of burnt fruit is also present now as is some rancio.

Palate: The entry is sharp and hot, with the tip of the tongue taking the brunt of the heat. There is a bit of butterscotch on the next sip which is paired with vanilla cream and Sherry-seasoned oak.

Finish: The finish is medium length and quite bitter.

Formula 4: “Dark” rum

Appearance: Dark mahogany to brown. A swirl yields a set of evenly spaced fast legs.

Nose: Butterscotch makes itself known, smelling exactly like a hard candy. Further hard candy imagery arrives in the form of grape and cherry. Beyond the fruit is a hint of vanilla.

Palate: The mixture jumps onto the palate with a crushing blow of fake fruit and butterscotch. Sad though it may sound, I have an instant flashback to my Spiced Rum Challenge, in which I tasted the same flavors in multiple “spiced rums”. The sweetness is mid-range, and lowers the perception of heat but not bitterness.

Finish: The bitter finish is carried by hard candy fruits.

Clearly I’m not ready to start a career as a professional fake rum blender, but the exercise was nonetheless successful in unpacking the flavors and sensations derived from several common ingredients in the blender’s toolkit. It’s actually pretty remarkable how close I was able to get to the Central American style on the first try.

I would encourage enthusiasts wishing to train their palates to detect these adulterants to re-create this experiment for themselves. One could also add each ingredient to white rum separately to isolate each compound organoleptically (a fake rum nosing kit, if you will). Once you develop the ability to separate exogenous ingredients from endogenous, your critical rum tasting abilities will be forever changed.

[Note: the sugar in the tables above was 1:1 simple syrup]

Part III: The Regulatory Side of Additives

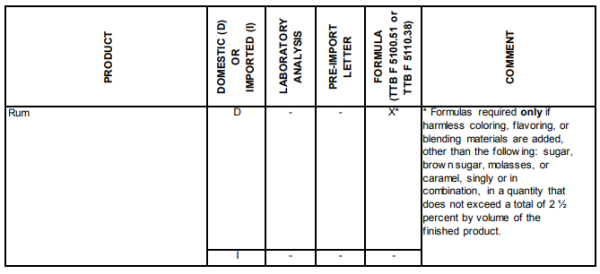

Earlier I used the word “unscrupulous” to describe producers of flavored products masquerading as aged rums. That is of course just my opinion, and in their defense it should be said that adding flavors to rum is legal in the United States providing the additives meet certain criteria, and they don’t exceed 2.5% by volume. Lovers of fallacious arguments would typically inject here that this is a “historical practice” among many rum makers, which while true is simply not a valid argument for its continuation.

That said, what can be legally added to rum, exactly? The answer is more ambiguous than you might hope. Of course the United States government explains things in a way that only a career bureaucrat could love, but if you want to get nerdy about additive regulations here in the States, read on.

Excerpt from Chapter 7 of The Beverage Alcohol Manual (BAM), A Practical Guide, Basic Mandatory Labeling Information for Distilled Spirits, Volume 2, April, 2007

There are a number of ways the TTB explicitly allows producers to adulterate their rum, and the main way is with what they term “Harmless Coloring/Flavoring/Blending Materials” or HCFBM. The TTB says HCFBM can be:

- An essential component of the particular class and/or type of distilled

spirits- Example: spice in a spiced rum

- Not an essential component but are, through established trade practice,

customarily used in the particular class and/or type of distilled spirits

PROVIDED THAT the total addition of coloring/flavoring/blending materials

does not exceed 2½% by volume of the finished product [that’s 18.75 ml in a 750 ml bottle].- Example: caramel color and Sherry in blended whisky

In terms of flavoring materials, these include:

- Essential oils

- Oleoresins

- Spices

- Herbs

- Fruit Juices/Concentrates

- Commercially prepared flavors including essences, extracts, blenders,

infusions, etc.

As for blending materials, these include:

- Sugar

- Wine

You’ll also notice in the chart above, CFA type 1 and 2 are allowed. What are those?

- Type 1: All natural color/flavor ingredient

- Type 2: Natural and artificial flavor ingredient containing not more than 0.1% artificial topnote*

- Flavors containing not more than 0.1% artificial topnote are considered natural when used in alcoholic beverages. The calculation of the amount of artificial material does not include artificial vanillin, ethyl vanillin, artificial maltol nor ethyl maltol.

- TTB has limitations for artificial vanillin, ethyl maltol, artificial maltol and ethyl maltol in alcoholic beverages. If these limitations are exceeded, the finished beverage will be considered an artificial product. The limits are:

- Vanillin: 40 ppm [vanilla]

Ethyl vanillin: 16 ppm [vanilla]

Maltol: 250 ppm [caramel, butterscotch]

Ethyl maltol: 100 ppm [caramelized sugar, cooked fruit]

- Vanillin: 40 ppm [vanilla]

*The TTB does not define “topnote”.

Perhaps the most interesting piece of the chart above is the “X” denoting that none of these additions need be disclosed on the label. Given where we are in terms of disclosures in food labeling, I find this a bit shocking. (And if I were adding nut extracts to my rums, I’d be very concerned about inadvertently killing someone with a nut allergy.)

You may hope to find a list of allowed additives here, but the list is just too long to publish. The most important criterion is an approval from the Food & Drug Administration. Barring a specific approval, the ingredient need only be “generally recognized as safe“.

The biggest problem from where I sit is the government’s opinion that ingredients considered to be non-essential but customarily added to rum can comprise as much as 2.5% of the product by volume, yet those ingredients do not need to be disclosed to the consumer. Depending on what the producer admits to on their application, the TTB may require a “Formula Approval”, which in theory compels the producer to admit adding non-rum ingredients besides sugar, brown sugar, molasses, or caramel. One might assume the formulations could be requested thorough a freedom of information act request, but the tax code specifically prohibits their disclosure.

It would seem that in order to achieve for rum the truth-in-labeling standards we’ve come to expect in food, the TTB would need to first enumerate what those customarily added non-rum ingredients are. I requested same from the TTB, but did not hear back by press time. Should they provide a list, I’ll add it here when received.

Another common sense change would be for the TTB to compel producers to list any potential allergens on the label as is the case in some other countries. For example: “contains almond extract”.

We needn’t know the exact formulation of every product, but consumers should be entitled to some basic information about what they’re ingesting. Forcing producers to list their ingredients would help make beverage alcohol safer and enable consumers to make more informed choices about their alcohol consumption. Until then, we’ll remain in search of the truth.

Hello again Josh, and thanks for diving into a VERY convoluted subject. A tour de force!

As we should all be aware the regulations – as most are – are heavily lobbied by the industry. The parsing is minute and misleading.

The most common misrepresentation is that flavoring, etc. can be done legally (and without labelling) up to 2.5%. But the catch? Under what is called “Established Trade Practice”. We are thus misled to believe that since some distillers add various adulterants and flavorings such that this is assumed to be trade practice, and ergo…. legal!

NOT. Not legal. Actually “Established Trade Practice” has ai well established meaning. Simply put, the practice must be standard and expected to the point that any product made otherwise, it fails to meet the standard of identity.

Thus, if adding prune extract is “established trade practice” it means that ALL “rum” must be made using it, or – it is not “rum”. Example of an “established trade practice”: when you go to a dealer who is selling an automobile you expect it to be delivered with wheels. The dealer does not have to advertise that his Ford Focus is being “delivered with wheels”. You expect that, why? Because selling a car with wheels is Established Trade Practice”.

Indeed if you buy that car you would be furious if it were delivered without wheels, and you would be right. The same is true for rum: if adding prune extract was “established trade practice” you would expect all rum to be so produced. This is not true, ergo the 2.5% rule (applicable to all spirits) does not apply.

Indeed if flavorings are added to a particular rum (outside of established practice), this case is covered the standards of identity for “flavored rum” which mandates that the primary flavoring must be identified and yes, labelled, eg “Prune Surprise”.

Great article, and great work as always.

it’s one thing to claim that adding flavor to rum is a common practice but another to deny or obfuscate the truth from the general populace.

If it’s such common knowledge then why aren’t more people aware?