How Does Water Quality Affect Rum Production?

Whisky marketers have long touted water as being critical to their products’ taste and purity. Be it a pristine mountain stream or precious artesian spring, it seems every Bourbon and Scotch producer has some amazing and uniquely pure water source that carries with it beneficial minerals that make their whisky what it is. Yet with rum, water’s importance is rarely touch upon. Why is that?

As we begin to answer that question, we must first acknowledge the fundamental difference between whisky and rum production: grain requires an enzymatic conversion to turn starches into fermentable sugars, while sugar cane and its byproducts do not.

Water is essential for enzymatic conversion, as the grain must be hydrated to unlock the starches, and trace minerals within the water like calcium and magnesium are necessary co-factors for some important enzymatic processes. But once mashing is complete, grain is on the same page as cane: ready for fermentation. Yeast is added and the sugars are converted to alcohol, carbon dioxide, and heat.

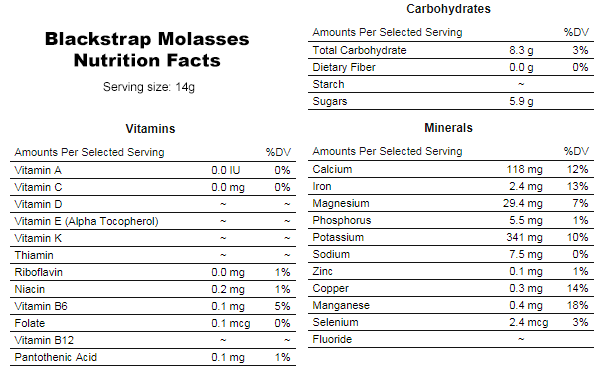

During fermentation, water’s role in making molasses wine is critical. After all, for every gallon of molasses, as much as six gallons of water is needed for dilution. But beyond dilution, what does water bring to the fermentation process? To answer that, let’s see what’s in molasses and note any deficiencies for healthy fermentation.

With just a quick glance, we can see that molasses looks like pretty great yeast food. It’s got plenty of sugar and a host of vitamins and minerals to support yeast growth and fermentation. The only downside is the ash content, which is usually around 1% in baking molasses like this, but can be as high as 30% in molasses slated for rum production. Too much ash (and other non-fermentable solids like gums) can inhibit yeast activity and negatively affect ethanol yield. Given that molasses is so nutritious, what qualities do distillers look for in their fermentation water?

Basically, the water needs to be wet.

Joking aside, there are some water components that are desirable, but the water needn’t be sourced from an idyllic mountain stream. As with whisky production, rum fermentation water should have no biological material, a pH just left of neutral, moderate hardness, low iron, a bit of calcium, magnesium and sulfate.

Of course in the early days of rum and whisky, distillers simply used what they had on-hand, and their results were correspondingly good or bad. The famed limestone aquifers of Barbados and Kentucky naturally filter out impurities like iron, for example (too much iron, and your spirit can turn black) so their water rightfully developed a reputation for purity.

Today distillers have the option to treat their water and make it conform to an ideal standard. I reached out to a few rum makers to see where they got their water for fermentation and how they treated it:

As you can see, the level of treatment corresponds to the potability of the water source. The cleaner the water, the less you have to treat it for use in the distillery (with the caveat that chlorinated water must be dechlorinated).

So essentially if you have fresh water of any type, you can make rum with it provided you treat it first, and if the water is deficient in a particular micronutrient, the molasses probably has it anyway. What then do distillers add to their rum washes beyond molasses, water, and yeast? And more importantly, could any of it be found in a theoretically “perfect” water source?

The most common fermentation additive in rum making is probably diammonium phosphate (DAP), which is used to supply the yeast with a concentrated source of nitrogen. Without adequate nitrogen, yeast can slow down or stop working, leaving behind valuable sugars and reducing alcohol yield.

If you find water with high nitrogen, you’re probably in an area with an agricultural runoff problem or industrial contamination, so this would not be a factor in water sourcing.

Some (usually smaller) distilleries may use additional nutrients to support healthy fermentation and to protect yeast from dying as the alcohol concentration in the wine increases. These additives include commercial preparations such as Lallemand’s Fermaid K®, which provides free amino acids, yeast hulls, unsaturated fatty acids, sterols, and micronutrients such as magnesium sulfate, thiamin, folic acid, biotin, calcium pantothenate, as well as other vitamins and minerals.

Water can provide minerals like magnesium sulfate, but the need is minimal to non-existent given the amount present in the molasses. Therefore additives like Fermaid K® are more likely to make up for molasses deficiencies rather than water deficiencies.

So besides fermentation, where else is water used in the distillery?

Water is used to make steam to drive the stills, it’s used in the condenser to cool the alcohol vapor as it comes off the still (unless the distillery employs a closed-loop glycol chiller), it’s used in the cooling tower (if they have one) and it’s also used to clean the stills, tanks, and floors.

Clearly distilleries use a lot of water, but aside from the scaling potential of the water in the boiler and on the condenser (mineral deposits on these surfaces reduce heating and cooling efficiency) and the number of cycles it can survive in the cooling tower before being disposed of, the quality required in these applications is again nothing too special.

That leaves us with the final application for water use in the distillery, which is perhaps the most important as it’s the only ingredient added post-distillation: proofing water (the water added to rum to bring it to bottling strength). Given that this water will be directly consumed in a mixture with the rum, it must be completely free of biological material. Likewise, the water must be free of multivalent cations (hardness). If the water has significant hardness, it could both add mineral flavor and remove rum flavor by precipitating congeneric material out of solution. Likewise the water must be relatively free of anions such as chloride and sulfate, which could also negatively impact flavor.

As with the fermentation water, I asked the same rum distillers how they treated their proofing water:

Clearly the goal for all of these distillers is to add nothing but pure H2O to their rum. Both deionization and reverse osmosis remove essentially all of the anions and cations from water, leaving it with no minerals or discernible taste. So in what’s arguably the most critical application for water within the distillery, the composition and organoleptic qualities of the source water have zero significance (this is true for every just about distillery on the planet, by the way). The goal for proofing water is not to find the most pure or marketable source, but to create water with an absence of taste.

With our analysis complete, it’s clear that having the right amount of water is far more important than having the right kind of water at a distillery. Fairly rudimentary water treatment technologies can turn the world’s worst water into the world’s best, thus the chemical composition of the source water and its associated organoleptic qualities are far less important than in years gone by.

Furthermore, even distilleries with famed local water quality now treat their fermentation water in some way, and the water they add to their spirit prior to bottling is tasteless and ion-free. That won’t stop the whisky marketing folks from touting the qualities of their water source, but we can now definitively say it hasn’t actually mattered in a hundred years or so.

Editor’s note: Special thanks to the folks at Demerara Distillers, Foursquare Distillery, Trinidad Distillers, and Worthy Park Estate for sharing their water treatment methodologies.

I have never thought about how water quality relates to rum production. I wonder how big of molasses tanks rum production facilities have. They must be huge so that the production is uninterrupted.

A very helpful discourse, especially in helping to answer V eront the question regarding the best source water for rum making.